| The girl likes

sports, but her school has no sports program for girls. In

seventh grade, she heads a petition drive, requesting the school

board to start girls basketball. This petition drive is

conducted decades before photocopy machines, computerized word

processors and laser printers.

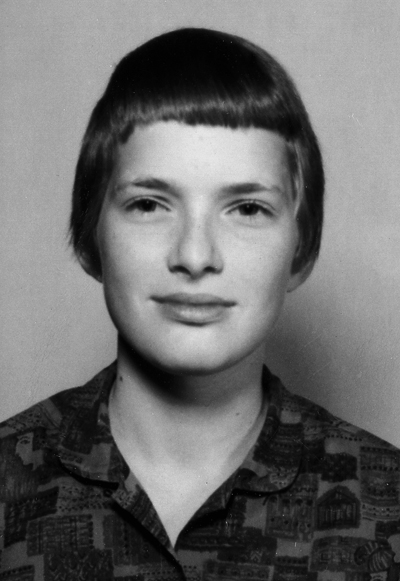

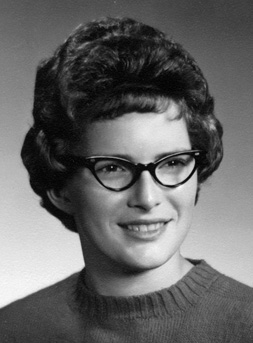

As a child and young adult, the girl often thinks of herself

as a troublemaker. She does not realize that her family and

school do not have adequate outlets for her energy . . . nor has

it dawned on her that the circumstances at home and in her rural

community contribute to her restlessness. Nor does she value her

perceptions. Perceptions that see injustice.

|

|

|

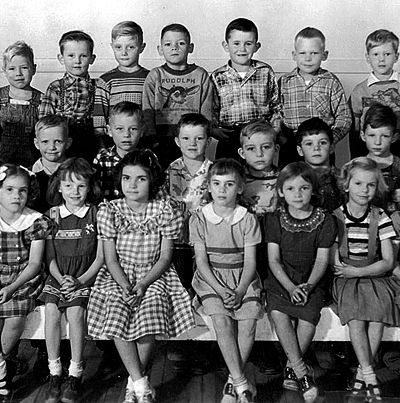

At the beginning of each school year, the grade school teachers

ask the boys to go to the first floor supply room to bring back

the stacks of textbooks that will be distributed to the students

for the year. The girls are to remain seated at

their desks. In sixth grade, for physical education, the head

high school basketball coach comes to the classroom early and

gets the boys. The guys go to the locker room, change into their

white gym shorts and T-shirts and put on their Converse tennis

shoes, then have a full-scale class in the new gym on the basics

of basketball. Near the end of the P.E. hour, the sixth-grade

teacher takes the girls to the gym, lines them up in single

file, in their school clothes (skirts and dresses) to shoot free

throws at one of the side baskets. |

|

What miffs the girl even more is that part of her hour of P.E.

has been robbed. It is a disgrace, like being in prison,

to sit in that sixth-grade classroom on the second floor near

the superintendent's office two-thirds of the P.E. hour while

the boys get their workout with the head coach. But to add

insult to injury, the teacher requires the girls to count two

points for each free throw they make. And the teacher does not

acknowledge the girl is right when she says a free throw counts

for only one point. |

| The girl and two seventh-grade classmates write the petition on

school-lined paper out of a spiral notebook and approach the

other seventh-grade girls in the hallway during the noon hour.

They get eleven signatures which means that over half the girls

in the class support their efforts. The list is written in

pencil along the left margin of the page under the simple

sentence across the top. It is in the best of junior high

language and contains no phrases of "whereas and thereby." It is

less complex, but only by a degree, than the statement that the

nation and state refuse to endorse in her adult years that would

have ensured that opportunity under the law would not be denied

due to one's gender. |

|

These girls have not heard the term

"suffragette" nor do they know their school had sported a girls

basketball team in the early part of the century. The

obstreperous one has never seen the photograph of her great-aunt

and teammates, lined up in their bloomers and sailor shirts,

holding the basketball, painted with white letters that say "RHS

1908."

|

|

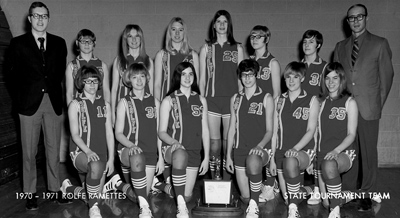

Nor can she predict, that her youngest sister,

ten years behind her, will be a starting guard and go to the

state tournament with the school's basketball team while she is

in the early part of her career teaching physical education in

Duluth, Minnesota. |

|

These seventh-grade girls, in a town of 800, in northwest

Iowa, who seek a single page full of signatures over the noon

hour, know they are getting the short end of the stick. They

make their petition specific. They address the letter to the

school board and begin with the salutation, "Dear Sirs." Their

statement follows, written in a mere sixteen words. "We, the

undersigned, request that Rolfe Consolidated Schools begin to

have an interscholastic girls basketball program."

The eighth-grade boys lure the group into letting them help

with the petition. The girls do not trust the boys, but the boys

assure them of their good intentions. However, when the girls

hand their sheet of paper to the boys, the boys tear it up.

|

| The girls start another petition and mail it to the board.

Mr. Ralph Mortensen, the superintendent at the schools

throughout the 1950's, the years that the obstreperous one is in

kindergarten through junior high, calls her into his office to

relay a message from the board that it has gotten the petition.

He says, "Now this doesn't mean that the board says you can have

basketball or not. It just means that they want you to know they

got your petition. However, it may be that as you get older, you

will realize that there are good reasons why girls shouldn't

play sports." The girl says nothing. Fortunately, two years

later, her school consolidates with the Des Moines Township High

School that already has a girls basketball team. |

|

|

Mr. Mortensen moves to another school. The

girl is in ninth grade and gets her opportunity to play

basketball. There is uncertainty. The players from the

township school have competed before, but the others do

not have an inkling of what to expect either in practice

or at an actual game. There is a full range of girls,

freshmen to seniors, who have long been denied the right

to play but now are anxious to have their day on the

court; however, they go through the early weeks of

practice, not knowing who will make the cut and get to

take home uniforms. There is also smugness. She does

exactly as she is told and catches onto drills easily

and is able to run the plays smoothly. She is a bit

cocky, anticipating how well these plays will work

against other teams. |

|

|

The day comes for the coach to hand out the uniforms. He

stands in the center of the gym while the girls sit along the

end line. He reads the names of the players one at a time. Those

who make the cut join him in the center circle. Those who don't

get to go home. The night of the opening game comes. It's a road

trip. The girl gets to play most of the junior varsity game. Not

only does her team lose but she feels lost in the locker room

after the game. She is surprised

when the coach comes to her and says she should prepare to join

the varsity squad for its game. Even though she sits on the

bench, the idea of making the varsity gives her a spark of joy

in an otherwise desolate evening.Beginning her sophomore year, she gets to be a starter on the

varsity squad because one of the leading scorers who had come in

with the township team had gotten pregnant and had to leave

school. However, in all her high school years, the girl's team

wins only a handful of games, playing against successful teams

in the conference who had decades of basketball history behind

them.

There is one game, a road trip to Twin Rivers, that is

devastating, not because it is that much worse than other games,

but because the pressure of losing so many times has accumulated

to a breaking point. No matter how well practice has gone or how

much her team has improved, it cannot penetrate the opposing

defense. The Twin Rivers guards anticipate every move and are

not fooled by a head or body fake. They prevent the forwards

from entering the free throw lane and getting close to the

basket. They block shots and intercept passes. In essence, they

shut down whatever offense that the girl and her team mates have

developed. After the game, the girl goes by herself to a side

section of the locker room. She is in no hurry to get dressed

and does something she has never done before. She sits on the

floor in the middle of a pile of towels, duffle bags, street

shoes and clothes, her legs folded with her knees tucked against

her chin so she can fit between the row of metal lockers and the

dressing room bench. It is an awkward place to be but the only

place to withdraw. She begins to cry then bawls. Her face is

red. Tears stream down her cheeks. Eventually she picks herself

up, showers, dresses and heads for the bus with the rest of the

team. Nothing is said. Several days later at home, after the

girl cleans her room and does her other required Saturday

household chores, she scampers downstairs to the living room to

check in with her mother before heading out doors. Her mother

stops her and wants to talk. She says she has heard that the

girl cried after the game at Twin Rivers. The girl wonders how

her mother knows what happened but says nothing. Her mother

continues, "We don't cry about things like losing a ball game."

The girl remains attentive, albeit quiet, a proper amount of

time for the conversation to conclude without being abrupt or

rude, then continues on her way to be out and about the farm

with her horse.

|

As a high school senior, she realizes she has only

one year remaining to make good at basketball. One night

late in the fall, after the basketball season begins,

she goes out by the garage where there is a post and

basketball basket at each end of a rectangular, concrete

parking area. It is the family basketball court. In the

cool, harvest air, that has a hint of winter, she

practices long and hard. She does lay-ups, making a loop

from the basket at one end to the basket at the other.

She is concerned about how little spring there is in her

jump. Each time around, she tries to leap higher but

cannot go higher. The rest of the family has gone to

bed, but she stays out under the yard light. |

|

|

One more lay-up along the baseline, she says to herself, and

she will go in. She goes for the lay-up, but comes

down hard, turning her ankle on the edge of the concrete where

it drops off and becomes grass. She is in great pain, swears at

herself, then manages to hobble into the house and up the stairs

to her bedroom. The next morning, her ankle is swollen and

purple. She cannot stand on her foot or get ready for school.

She has to tell her mother. A trip to the doctor. X-rays, an ace

bandage and crutches, Epsom salts and hot water. The ankle

begins to heal. The coach wraps it with many layers of adhesive

tape. The girl plays but sprains her ankle two more times during

the season, once at practice and another during competition. The

game at Pocahontas is going well, but she trips over her own

feet, turns the ankle, and crashes to the floor. She slams her

sweaty palm on the varnished wood in anger and frustration. She

gets to her feet, is helped to the bench, puts ice on the ankle,

and sits out the rest of the game. She is put on crutches again

and misses more games. As she sits as a civilian in the

bleachers and watches her teammates in action, she isn't sure

she wants to play any more. The season is sliding by with little

prospect of winning, so what is the use. Her basketball career

is nearly over with no sign of success.

The girl returns to competition, and her team wins three

games before the season is over, but she realizes it is hard to

make the short jump shot. It's especially frustrating when she

is in the open under the basket. She runs the play perfectly,

faking out her guard, rolling off the screen, moving to the left

of the lane, getting the long pass from center court, but

clutches. She sees the rim. A big circle. An easy shot. But in

that split second before she releases the ball, she thinks,

"I'll probably miss." And she does.

At fifty, she goes to her school's all-class reunion where

multiple generations of her hometown clan gather. The only

speaker is Mr. Mortensen. She wants to stand up, like at a press

conference, and demand that he respond to her question. To

insist that he explain what he meant by those remarks he made in

1957. To demand an apology. But of course she doesn't. What

would her classmates think? What would her parents think? What

would she think of herself?

Rolfe High School 1963 girls

basketball team. Front row, left to right: Linda Leadley,

Diane Callon, Joann Bennett, Phyllis Pedersen, Debra Johnson,

Kaye Smith, Helen Gunderson, Shirley Bennett, Carol Biedermann,

Chris Trimble, Geraldine Baker, Diane Trimble. Back row:

managers Ann Cleal and Sharalyn Wolf, coach Jack Head. |

|