|

Obituary

More about Verle and Velma

|

|

|

1995

|

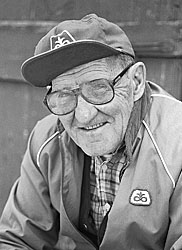

VERLE DUANE HOWARD

Verle D. Howard – age

85, of Rolfe, passed away Saturday, August 1, 2009 at the Rolfe Care

Center. Verle Duane Howard was born February 22, 1924, at Jolley,

Iowa. He was the son

of Harry and Marian (Patterson) Howard. He attended school in Ware and

Havelock and graduated from Pocahontas High School in 1941. He attended

college in Ames before enlisting in the U.S. Air Force where he served

from 1943 – 1946. He served in North Africa, Egypt and Italy. On May 19,

1947, Verle married Velma Benton at the Rolfe United Methodist Church.

To this union six children were born. Verle worked for Corn Belt Power

in Pocahontas and Humboldt plants and for Voice of America overseas as a

power plant supervisor in the Philippine Islands and Tangier, Morocco.

In 1962, Verle and Velma settled on the farm near Rolfe, retiring in

1994. In 1998, they moved into Rolfe.

Verle was a member of the Shared Ministry of Rolfe where he served on

the church board and the American Legion where he was a past commander.

Survivors include his wife, Velma of Rolfe; daughters, Hope (Brian)

Hutchins of Carson City, NV; Kelly (Dale) Hartman of Britt and Karen

(Carl) Leyba of Thermopolis, WY; 14 grandchildren; six

great-grandchildren; in-laws, Terry Hayes of Aiea, HI; Gail Seeger of

Riverside, IL and Mary Howard of Minneapolis, MN; and many nieces &

nephews.

Verle was preceded in death by his parents; sons, Randy and Monte;

daughter, Joy; twin sister, Doris Hepperle; sister, Genevieve Wilson and

brother, Garth Howard. |

|

MORE ABOUT

VERLE AND VELMA

Verle and Velma were part of

the documentary project

that RHS alumni Web site editor, Helen Gunderson, has been doing since the

early 1990s about the rural neighborhood where she grew up between Rolfe and Pocahontas.

The Howard farm is a mile west of the Deane Gunderson farm.

VERLE AND VELMA'S FARM

(a portion of Helen's book about Verle and Velma, updated in about 2004)

PDF file |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The following are transcripts

and/or MP3 recordings from an oral history interview that Verle and Velma

did with Helen in 1992. A portion of the material includes

comments by their across-the-road neighbors, Marjorie and Paul Harrold,

about Verle and Velma from a separate interview. |

|

|

PONIES

listen

to mp3 audio

length 2:54Velma: When Karen and Kelley

were small, they wanted ponies. Don Shoemaker from Rolfe advertised two

ponies. So we bought the ponies from him. I only remember Buttercup’s name.

Anyway, at that time, we had fences around the buildings, and there was a

wire gate. Those ponies could figure out how to unhook that gate. Every time

the kids tried to pasture them in the area between the house and the barn,

those ponies would work around until they could get out. And away they would

go, back to Don Schoemaker’s place. Then Verle would take the girls in the

car and go to town. They would find the ponies, and the girls would have to

ride the ponies home or they would hang onto the reins and make the ponies

run along behind the car. Verle would just mutter and storm all the way

home. Finally, the kids didn’t ride the ponies anymore, and the ponies were

old. One of Verle’s cousins, Gary, who lived south of Palmer, was here. He

had little girls, and those little girls spent the whole afternoon riding

the ponies. So Verle gave him the ponies, and he took the ponies home. Gary

kept the ponies until they died of old age. He, too, cussed Buttercup

because she was always the one that managed to get out.

Verle: We even had a milk cow.

Velma: We had a milk cow for almost three years. It

was Randy’s chore to milk the cow. And then Randy went to Washington, D.C. —

he won an REC trip in his junior year of high school — and Verle had to do

the milking. The old cow kicked him out of the barn, and she was shipped to

the locker and butchered after that.

|

|

|

CHICKENS

listen

to mp3 audio

length 3:20 |

|

|

SHELLING CORN

listen to

mp3 audio

length 2:18 |

|

|

THRESHING OATS

listen to mp3 audio

length 2:08Helen: What do you

remember about threshing along this road? Verle: When

we moved here in 1940, they still ran threshing machines, and everyone who

had grain furnished a man either to haul grain or to haul bundles. The

Grants owned the threshing machine at first. Then my folks bought a

threshing machine when Grants decided to quit, and we threshed for several

years. That was when you really had the neighborhood working together. The

women always served great big meals — wherever you were, they had to feed

the crew. The crews had six or eight bundle racks, which meant six or eight

men hauling bundles and pitching them into the threshing machine and maybe

one or two spike pitchers in the field that helped the fellas load their

bundles. Then, of course, they had the grain haulers that hauled the grain

from the threshing machine to the farms and elevated it into the cribs. In

some cases, they might even scoop some into a bin for the farmers, but it

entailed a lot of work. You cut the grain in bundles, shocked it, let it dry

out — or cure — and then you threshed it. When the threshing was all done,

the crew always had a great big picnic. That was “settling up day.” You

always paid the owner of the rig for the threshing. I think they got about a

penny and a half or two cents a bushel for threshing it. |

|

|

Verle with his 706 Farmall and mounted

mounted cornpicker harvests corn in 1992,

his last year of farming before retiring.

Click on image for larger view. |

|

|

|

LIVING SIMPLY Helen: My understanding from what

you have told me is that Verle’s parents owned a farm in Calhoun County but

lost it in about 1930. Then they rented near Ware about the time he started

school. After that, they rented near Havelock, and then moved to a place

southeast of Poky before buying this farm in 1940, the year before he

graduated from high school in Poky in 1941. I’m wondering, Velma, did your

folks lose their farm, too?

Velma: My parents didn’t “lose” a farm. They sold.

They had bought my mother’s family farm in Missouri, and they were just

making ends meet and couldn’t keep the payments up, so they sold the farm.

Dad was a hired man for one year, and then he managed to rent a farm down by

Lanesboro. From there, they went to Jefferson and rented for several years

before they bought the farm at Curlew. They always had to struggle to make

ends meet, or at least that’s the way I remember it.

Helen: When you graduated from high school, Verle,

did you ever think you would end up back on this farm?

Verle: Yeah, I had a slight idea that I would, and

more so than ever after I traveled around the world for a few years.

Helen: Why is that?

Verle: For one thing, you are your own boss, pretty

much. You make your life what it is, and that’s the way it is on the farm.

You have nobody breathing down your neck. (chuckle) If you do, you can tell

them to go chase whatever they want to, and it doesn’t make any difference

to you. It doesn’t hurt your business a damn bit.

Helen: How much are farmers really their own boss

when you consider all the government policies and other things that seem to

go against farming?

Verle: Well, at least you still have choices. You

don’t have to enroll in the programs. You’re still more your own boss than

punching a time clock where they have to meet production schedules.

Actually, you make what life is on the farm for yourselves. I can see where

it would get pretty tough on the farmer if you didn’t want to do anything.

(chuckle)

Helen: How would you describe the lifestyle that you

have cut out for yourself here?

Verle: I wouldn’t want to change it.

Velma: Our operation is small by normal standards.

And if we had a family, there is no way we could operate the way we do. We

would have to have more land or another job. But when you are two old people

with rocking chair money, you don’t need to farm a lot of land — just enough

to keep you active.

Helen: You two have often said that you are holding

things together with baling wire. Could you explain what that phrase means?

Verle: When your machinery starts giving you little

problems when you’re in the field, a piece of wire will tie it together

until you get done — that’s what we call, “We’re running on baling wire.”

Velma: When I was growing up, we used that term. When

machinery wore out in those days, they couldn’t afford to trade it in — and

we can’t now on our 160 acres. So we hold the equipment together with baling

wire for one more year. You repair it rather than trading it in on new; we

repair it.

Verle: And then you say, “We baling wired it together

for another year.”

Velma: If the baling wire holds out, we’ll be OK.

Verle: I have the required equipment to farm. When I

quit farming a half section, I never sold any machinery.

Velma: You have bought a different picker.

Verle: But fundamentally, I still have the equipment

I had when I was farming a half section. I do all my own maintenance on it,

and it hasn’t really cost me anything. |

|

|

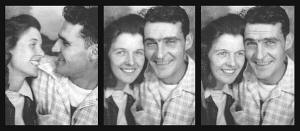

Verle and Velma

click on photo for larger view |

|

|

|

MEN, WOMEN, AND COUPLES Velma: Verle teases me

all the time about having “his dog house.” When we got the new recliner,

rather than burn the old one, he put it down in the chicken house so he

could have his “dog house.”

Verle: Well, I do a lot of work down there in the

wintertime. I build toy chests and ...

Velma: And then, our daughter, Hope, and her husband got a new TV,

and again, rather than throw it away, they brought it to the farm for the

chicken house, but it never got to the chicken house. It got put in the

playhouse. That’s why he has two places to go — he has the playhouse and the

chicken house.

Helen: So, are you in charge of the house?

Velma and Verle: (chuckle)

Velma: I guess so.

Verle: You better believe she is.

Velma: I don’t spend any more time in his chicken

house than I have to.

Verle: I clean my shoes and take my boots off at the

door of the house.

Velma: Well, doesn’t everyone?

Verle: I can’t even sneak in the door and cross the

kitchen and get a cup of coffee with my dirty shoes on.

Helen: How was it that you started wearing

suspenders?

Verle: Well, every time I got off the tractor or got

on the tractor, I had to pull my britches up. I got so sick and tired of it

that I said I was going to get some suspenders. And I was in the Farm and

Home Store one day, and I saw these suspenders. I put them on and haven’t

taken them off.

Helen: Do you call this farm your homeplace?

Velma: This is the homeplace to the kids because

Grandpa and Grandma Howard lived here, and now we’re here. And when we talk

family reunions, which we have been trying to have every other year at

least, they always think it should be at the farm.

Helen: What’s that like?

Velma: Sheer bedlam. (chuckles) I’m not exaggerating

one bit. We rented campers about four years ago, and the kids were all here.

We set up a tent, too.

Helen: What do the grandkids like to do?

Velma: The adults sit around and eat and visit and

tease and generally enjoy themselves. And we play games with the kids. The

grandkids like to dig out all the old games that their parents had when they

were that age, and they make forts in the bales of straw in the haymow. They

like to play badminton, horseshoes, basketball, volleyball, and whatever

strikes their fancy. The grownups, usually the men go golfing, and the women

sit around and swear because the men don’t come home. (chuckle) You know,

like most families. |

|

|

|

NEIGHBORING Helen: What can you tell me about

neighboring, especially since you live just across the road from Velma and

Verle?

Marjorie Harrold: Verle’s folks moved there the year

before my folks moved here. There weren’t any better neighbors. Of course,

that was back when farmers worked together with haying, and they were

threshing yet, too. My dad and Verle’s dad did all kinds of things together.

That was the war years, too, and we didn’t have any help, so we had to

depend on our neighbors.

Verle: We get along, I would say, ideally. Paul never

bothers me. I never bother him, but if I need another hand, I just hold my

hand up, and he’ll be here. And it works both ways. For instance, if he is

out sorting hogs, and I go out of the house in the morning, it’s nothing for

me to go over and help him sort a load of hogs. By the same token, if I need

something, he would drop everything and come over. There are a lot of jobs

that I can’t do alone; I have to have two more hands. All I have to do is

let him know what I’m going to do, and he’s here. And you don’t even have to

let him know. He’ll come over and tell me.

This spring, I had some wet plowing that I had plowed, and

it was flabby. He came over and said, “Verle, why don’t you come over and

get my big disk and that big engine of mine and disk that spring plowing

again.” So he didn’t wait for me to go over and get his outfit. He brought

it up in the field and came in the house and said, “Well, Verle, come on

out, and I’ll show you the main points of this engine and how to operate it

and where to run the RPM.” So I disked 70 acres, and Paul came back over

again and said, “Verle, if I were you, I would hit that again, and then I

would hit it with your own little disk.” It gives you an idea of what kind

of neighbors you’ve got. I disked the whole field twice, filled the tractor

full of fuel, took it back over, and put it in his yard.

Velma: In the wintertime, Marjorie and Norine and I

get together, usually three times during the winter. We each take a turn

hosting and having coffee. If Marjorie stops over, it’s not an invited

thing. We drink coffee together when we happen to stop by each other’s

homes. We talk on the phone, maybe once or twice a week. We wave to each

other when we go to our mailboxes or when we are mowing the lawns. We

exchange recipes over the telephone. If she has some extra garden stuff that

she knows we don’t have, she brings us a sack, and if I have something, I

take her a sack. We don’t make a point of entertaining each other — we’re

just here. We each know that the other is there.

Verle: As a rule, we each know when the other is

gone.

Velma: We make a point of telling each other if we

are going to be gone, so we can watch their place and they watch ours.

Paul Harrold: When we want to go somewhere, we just

tell the Howards if we are going to be gone for a while.

Marjorie Harrold: We kind of watch. If anything looks

strange, we’ll see what’s happening.

Paul: It’s pretty hard not to look across the road

during the day when we are just an eighth of a mile apart.

Marjorie: We know what each other is doing.

Helen: It’s nice that you have similar standards in

terms of keeping your farms clean. Because you are so close, it would be

horrible to look over at someone else’s eyesore.

Paul: Well, I don’t imagine they like the pigpens

being across from their front yard.

Helen: I think the setup is nice because Velma and

Verle can feel like there are animals around but not have to have their own.

Marjorie: They can look over and see ours. (chuckle)

But sometimes on Sunday when the wind comes out of the north, it’s not so

good.

Paul: And I am sure in the summertime, considering

they don’t have their own livestock, they probably would just as soon not

have their neighbors’ flies, either. |

|

|

NEIGHBORLY HELP

listen to mp3

audio

length 1:11 |

|

|

|

|

PDF file of currently

available transcriptions |

|

|

|

Note: this page was hurriedly

assembled on August 3, 2009, from materials close at hand but not already formatted for

this Web site. Eventually, we will update the page and perhaps reformat it

to make it more user-friendly. |

|

|

|